We've all heard of, seen, and experienced muscle growth. It’s an integral part of being human and plays a vital role in our development from an early age to adulthood. Today, we’ll dive into the processes behind muscle growth, and how we can go about stimulating it. So, if you've ever wondered, "Hm, I wonder what makes our muscles growth." then read on. Let's dive in.

Muscle Anatomy

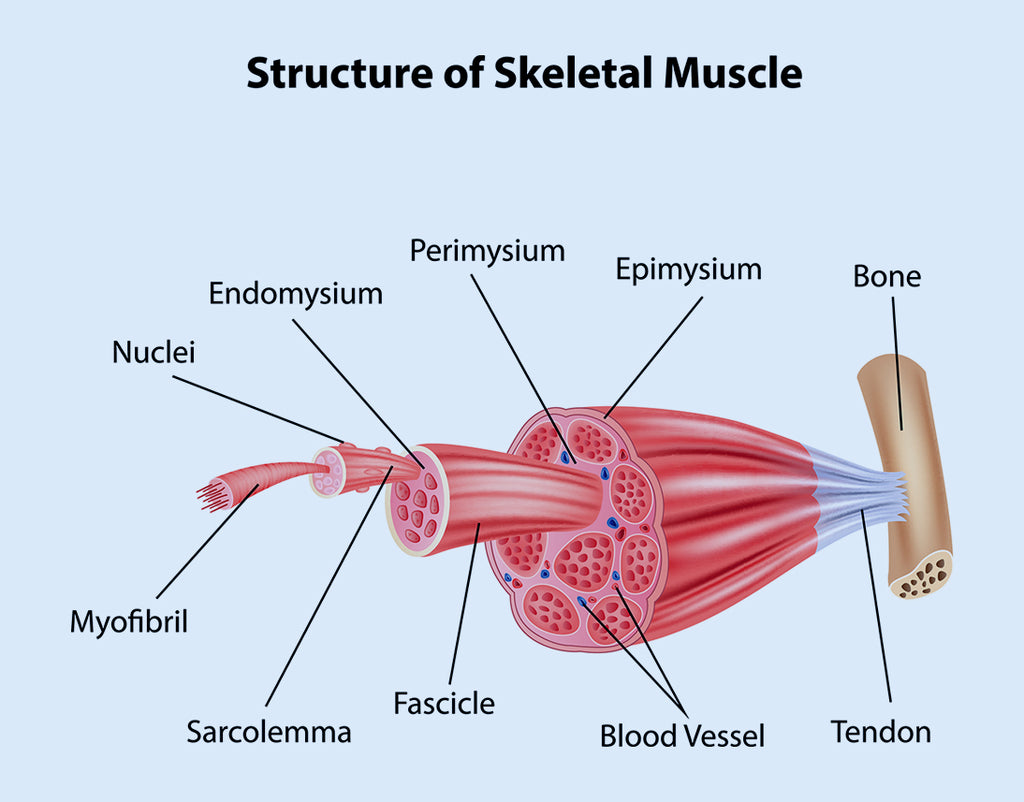

Before we dive into the types of hypertrophy, we first need to gain a basic understanding of muscle anatomy.

A skeletal muscle (or muscle belly, to be more specific) is made of multiple groups of muscle cells (fibers) that are bundled together and run parallel to each other. Each ‘bundle’ is called a fascicle.

Thanks to connective tissues known as tendons, our muscles most often attach to bones, at two or more spots. These are your origin (the site that doesn’t move during contraction) and insertion (the site that does move during contraction) of muscles.

When a muscle shortens (contracts concentrically), it influences the insertion point and causes movement.

Each muscle fiber consists of many myofibrils that collectively form it. The area surrounding myofibrils within each muscle cell is called the sarcoplasm. To go a bit deeper than that, we also have myofilaments – the components that make each myofibril.

So, it looks like this:

| Many myofilaments | a myofibril |

| Many myofibrils | a muscle fiber |

| Many muscle fibers | a muscle belly |

The Two Types of Muscle Hypertrophy

Now that we have a basic understanding of what a muscle is, let’s take a look at how it grows in size.

Myofibrillar Hypertrophy

During myofibrillar hypertrophy, we see an increase in the population of myofibrils (contractile units) within our muscle cells. This means that we improve the power output potential of our muscles while also growing them in size.

Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy

Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy refers to the increased volume of sarcoplasmic fluid within our muscle cells – a process that is independent of the accumulation of myofibrils.

A few Ideas on Sarcoplasmic and Myofibrillar Growth

Depending on our style of training, we will experience some degree of both types of hypertrophy. For example, you can experience a large increase in contractile units with small accompanying sarcoplasmic hypertrophy. You can also experience a significant rise in sarcoplasmic volume, with a slight increase in contractile units.

Bodybuilders, for example, experience much higher sarcoplasmic hypertrophy than, say, powerlifters. Olympic weightlifters, on the other hand, tend to experience greater myofibrillar hypertrophy.

But in almost all cases, we will experience both types of hypertrophy, at least in the long run. This is why strength gains (especially in higher repetition ranges) are such a great indicator of muscle growth – a larger muscle has a higher strength potential thanks to the inevitable accumulation of contractile units.

How to Make Muscle Growth Happen

Prevailing wisdom suggests that all we need for optimal muscle growth is to eat a lot, train heavy, and get enough sleep. Granted, these are the three fundamental elements of muscle growth, but the above examples are oversimplified ways of looking at the whole process.

The truth is, muscle growth is an intricate process, and you have to look beyond the basics if you want to optimize it.

With that said, here are some practical suggestions:

1. Training for muscle growth

The topic of training for muscle growth is vast, and no single solution will work for everyone. But, for the most part, we can follow these basic recommendations and achieve great results:

-

Train with adequate volume – between 10 and 16 weekly sets for large muscle groups and 6 to 10 weekly sets for smaller ones. As a rule of thumb, you should do less, rather than more. Only add more work if you see that you’re not progressing.

-

Train in a variety of repetition ranges to cause different types of stresses to your muscles and stimulate both sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar hypertrophy. This means, in the 5 to 12, 12 to 15 and even 15 to 25 ranges.

-

Use a variety of exercises to train different muscle groups from different angles. For example, use both horizontal and vertical pulling exercises for your back.

-

Mostly avoid training to muscle failure, as research suggests that it doesn’t help much, but causes too much fatigue and prolongs the post-training recovery.

2. Eating for muscle growth

Similar to the training aspect, we can also say a lot about the nutritional side of growth. But, for the sake of simplicity, here are some basic recommendations.

-

Maintain a small to moderate calorie surplus of 200 to 400 calories over your maintenance level. Theoretically, we can build muscle without a surplus, but being in one optimizes our growth rates as it provides us with enough calories for the many bodily functions while also leaving some for tissue growth.

-

Eat a balanced diet full of dietary fats, complex carbs, fiber, and at least 1.5 gram of protein per pound of body weight.

-

Ideally, try distributing your protein across four meals. Some research suggests that this allows for higher utilization of the amino acids, and less of them get oxidized for energy.

-

Pay some attention to your pre- and post-training nutrition – have some protein with carbs in the hours before training, and some once you’re done. This will help optimize your performance, kickstart the recovery process quicker, and allow you to replenish your lost glycogen more quickly.

3. Sleeping for muscle growth

As individuals, we all have different sleep needs. Some folks fare great on six hours of sleep per night, where others need 8.5 to 9 hours to feel normal.

The truth is, you should experiment and see what you need. As a general rule, you should aim for at least seven hours per night – ideally 7.5 to 8.

In research, sleep appears vital for optimal muscle growth, training recovery, and fat loss. Sleep deprivation negatively affects our athleticism, cognition, mood, and much more.

Hi, just a small problem in the text at 2.2.

I think its supposed to be per kg not per pound?

Leave a comment